Para bailar, para tocar, para gozar, para cantar...

Camila Viéitez, formada en Publicidad, Ilustración y Gestión Cultural. Ha sido, también, investigadora residente en el Museo Reina Sofía. A partir de su trabajo, mayormente ligado al diseño gráfico y a la ilustración, ha dado clase en el IED Madrid y realizado diseños para artistas amantes del karaoke como Cibrán, Columna Vegana o Joe Crepúsculo.

Edita fanzines desde hace años y en sus propias palabras "casi todas las cosas importantes de verdad que sé, las aprendí en el Liceo Mutante". Además de en Pontevedra, ha vidido en otras ciudades gallegas, Corinto (Grecia) y Madrid. Actualmente vive en Ourense.

Últimamente, combina encargos diseño con otras actividades más próximas a la gestión cultural y lo curatorial como el Archivo Plastimecos y la Residencia Méndez Méndez, un espacio en la montaña de Pontevedra destinado a la investigación artística que espera abrirá sus puertas este verano.

instagram.com/camila.vieitez

instagram.com/plastimecos

Camila Viéitez is trained in Advertising, Illustration, and Cultural Management. She has also been a resident researcher at the Museo Reina Sofía. Her work, mostly connected to graphic design and illustration, has led her to teach at IED Madrid and to design for karaoke-loving artists such as Cibrán, Columna Vegana, and Joe Crepúsculo.

She has been publishing fanzines for years, and in her own words, “almost all the truly important things I know, I learned at the Liceo Mutante.” In addition to living in Pontevedra, she has also resided in other Galician cities, Corinth (Greece), and Madrid. She currently lives in Ourense.

Lately, she combines design commissions with other activities more closely related to cultural management and curatorial practice, such as Archivo Plastimecos and Residencia Méndez Méndez, a space in the mountains of Pontevedra dedicated to artistic research, which is expected to open its doors this summer.

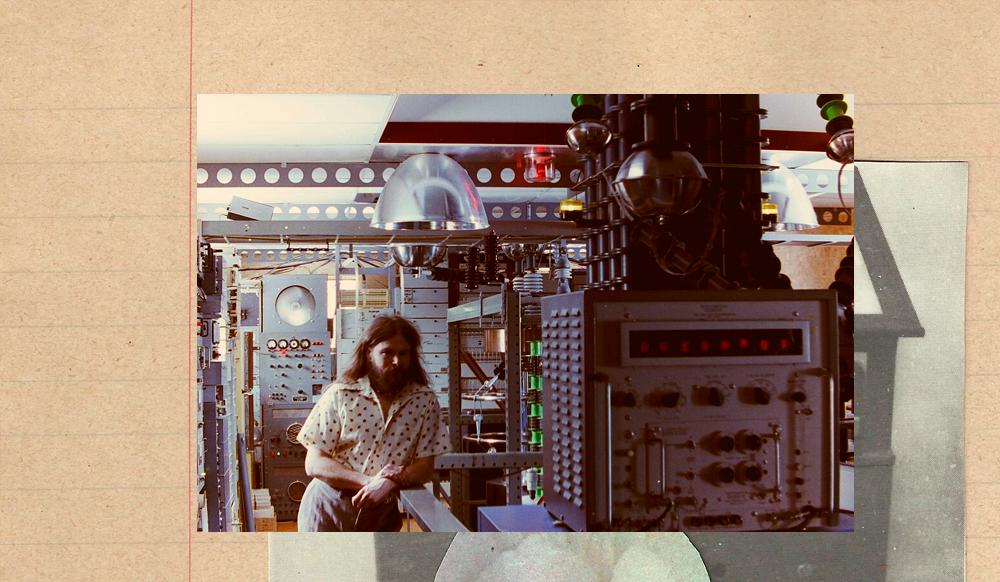

ITEM#1 Para bailar - John quería contactar con extraterrestres

En los años 70, John Shepherd construyó en su casa una antena capaz de enviar una señal de radio a una distancia dos veces mayor de la que hay entre la Tierra y la Luna. Desde su estación, Earth Station One, emitió durante los siguientes 30 años los más preciosos programas, sólo para las trompetillas de los extraterrestres que pudiesen estar sintonizando, con la esperanza de recibir algún día una respuesta.

A menudo, cuando pensamos en por qué no hemos recibido todavía (que sepamos) la visita de otras civilizaciones, nos lo explicamos diciéndo que, total, a que van a venir si aquí todo son guerras y maldades. Para luchar contra esa idea tentadoramente reduccionista, creo que puede ayudarnos escuchar las historia de John y sus emisiones, una absoluta demostración de toda la belleza de la que es capaz el ser humano acompañada de su exquisita selección musical y de la extrema amabilidad con la que el DJ y locutor se dirige a su esquiva audiencia. Ejerciendo el papel del mejor embajador terrícola que podríamos desear, no sé si el que hemos merecido hasta ahora, pero desde luego del que deberíamos esforzarnos por merecer.

Disfruta aquí y aquí de algunas de sus emisiones, y del corto John quería contactar con extraterrestres para conocer un poco más sobre él y su proyecto.

In the 1970s, John Shepherd built an antenna at his home capable of sending a radio signal twice the distance between Earth and the Moon. From his station, Earth Station One, he broadcast for the next 30 years the most precious programs, just for the little ears of any extraterrestrials who might be tuning in, hoping one day to receive a response.

Often, when we think about why we haven’t yet (as far as we know) received a visit from other civilizations, we explain it by saying, “Well, why would they come here?” To counter that temptingly reductionist idea, I think it helps to listen to John’s story and his broadcasts — an absolute demonstration of the beauty humans are capable of, accompanied by his exquisite musical selections and the profound kindness with which the DJ and host addresses his elusive audience. Playing the role of the best Earth ambassador we could hope for — perhaps not the one we’ve deserved so far, but certainly the one we should strive to be worthy of.

Enjoy some of his broadcasts [here] and [here], and the short film John Was Trying to Contact Aliens to learn a bit more about him and his project.

Item#2 Para tocar - El monje desnudo, Taneda Santôka.

Resbalo… y caigo

Todo en la montaña

sigue su curso.

Dice el traductor en sus comentarios sobre El monje desnudo que el tacto es el sentido que nos lleva al haiku y así, con el culo mojado, resbalamos hasta el Item #2. Santôka (1882-1940) fue un poeta japonés que vivió como monje mendicante gran parte de su vida. Su obra, compuesta por un buen puñado de haikus y algunos diarios, me emociona enormemente porque es, a mi entender, capaz de combinar una existencia absolutamente miserable con la admiración de la belleza y el relativismo de la propia presencia frente a la naturalez, acompañado, por si fuera poco, del ejercicio de un finísimo humor, Santôka parece demostrarnos, a través de sus poesías, que son estas, y no otras, las más eficaces herramientas para la supervivencia y el disfrute de las que disponemos.

Crepúsculo en calma

Lavando una olla

que ya está limpia.

No procede tampoco pegarte ahora una chapa sobre Santôka y los haikus, puesto que su virtud reside, en gran medida, en su capacidad de resumir, a la mínima expresión, imágenes enormemente evocadoras. Añadir sólo que Santôka forma parte de las primeras generaciones de haikistas de estilo libre. A estas también pertenece Masaoka Shiki, que, sin ser tan rock star como Santôka, también tiene poemas bien bonitos:

Sin hacer nada

La babosa de mar ha vivido

Dieciocho mil años.

I slip… and fall

Everything on the mountain

continues on its way.

The translator comments in The Naked Monk (in English there are other compilations) that touch is the sense that brings us to haiku, and so, with a wet ass, we slip down to Item #2. Santōka (1882–1940) was a Japanese poet who lived much of his life as a mendicant monk. His work, composed of a good handful of haikus and a few diaries, moves me deeply because, in my view, it manages to combine an absolutely miserable existence with an awe for beauty and a relativism toward one's own presence in the face of nature. As if that weren’t enough, all of it is accompanied by a refined sense of humor. Through his poems, Santōka seems to show us that these—his poems—are the most effective tools we have for survival and enjoyment.

Calm twilight

Washing a pot

that’s already clean.

Now is not the time to hit you with a lecture on Santōka and haiku, since their virtue lies largely in their ability to distill evocative images into the barest expression. I’ll just add that Santōka belongs to the first generations of free-form haiku poets. Among them is also Masaoka Shiki who, though not as much of a rock star as Santōka, also wrote truly beautiful poems:

Doing nothing

The sea slug has lived

eighteen thousand years.

ITEM#3 Para gozar - Las uvas pasas

Siguiendo la tan necesaria apreciación de los dones de la naturaleza, hablemos de uno de los más dulces: las uvas. Por lo general, hay consenso: nos encantan. Tintas, blancas, de piel dura de las que hay que pellizcar, o sin pepitas para comer de un bocado. Pintadas en los bodegones con cristalinos reflejos, pendiendo de las parras o colgando de la mano para ser comidas directamente del racimo en uno de los gestos más lujosos, decadentes y asequibles que nos ha dado la historia. ¡Qué satisfactorio sentirse una pícara robando una uva distraída de un frutero (cacharro, no persona)! y qué elegancia servirlas acompañando unos quesos en un platito. Reconocimiento aparte merece este fruto en su estado líquido: mosto, vino, vinagre, aguardiente y un largo etcétera.

Si bien el vinagre no está exento de controversia, aunque como cantaron los perfectos Esclarecidos: Hay bebidas dulces que destrozan el día y vinagres que alegran la comida, hay una versión de las uvas que todavía goza de menos simpatía: las pasas. Tan injustamente tratadas, tan arrugadas y llenas de dulzor, dispuestas a esperar eternamente en nuestra despensa hasta que nos acordemos de ellas. Las pasas, le pese a quien le pese, están ricas en los dulces, sí, pero es en los platos salados donde verdaderamente añaden una nueva dimensión de gozo. Ideales como contrapunto al amargor de algunas verduras, la acidez de algunas salsas y la sal de algunos quesos. Van fenomenal con pescados y carnes y aconsejo fuertemente incluirlas siempre que puedas, y tenga cierto sentido, en empanadillas, guisos y quiches, para, con un gesto mínimo, disfrutar de una vida más agradable.

Continuing our much-needed appreciation for the gifts of nature, let’s talk about one of the sweetest: grapes. Generally speaking, there’s consensus—We love them!. Red, white, with thick skins you have to pinch off, or seedless ones you can pop in whole. Painted in still lifes with crystalline reflections, hanging from the vine or dangling from a hand to be eaten straight from the bunch in one of the most luxurious, decadent, and yet affordable gestures history has given us. How satisfying it is to feel like a little rascal stealing a distracted grape from a fruit bowl (the dish, not the person)! And how elegant it is to serve them with cheeses on a little plate. Special recognition must also go to this fruit in its liquid states: juice, wine, vinegar, brandy, and the list goes on.

While vinegar might be a bit divisive (although, as the perfectly named band Esclarecidos once sang: "There are sweet drinks that ruin your day and vinegars that brighten your meal", there’s one form of the grape that enjoys even less popularity: the raisin. So unfairly maligned, so wrinkled and full of sweetness, forever waiting in our pantry until we remember them. Raisins—like them or not—are tasty in desserts, yes, but it’s in savory dishes where they truly add a new dimension of delight. Ideal as a counterpoint to the bitterness of some vegetables, the acidity of certain sauces, and the saltiness of some cheeses. They pair beautifully with fish and meats, and I strongly recommend including them whenever possible—and where it makes sense—in empanadas, stews, and quiches, to make life just a little more pleasant with minimal effort.

ITEM#4 Para cantar – Sé alegre, vive tu vida

Para cantar en un sentido literal, escucha Los Diablos (Rojos) que tocan así… y dan título a las cuatro categorías en las que se divide esta Pequeña Antimateria, enumeradas al inicio de su canción El Guapo. Un absoluto temazo que cumple lo que promete, acompañado de increíbles gritos y risas diablas de Lucho Carrillo. Imperdible.

Para cantar en sentido figurado, una idea que subyace en todas estos artículos y que ya hace 23 siglos supo resumir e ilustrar a la perfección la persona que realizó este mosaico:

El reciente hallazgo de un mosaico del siglo III a.C. en el sur de Turquía, con un particular mensaje (...), ha sorprendido a los mismos arqueólogos. «Sé alegre, vive tu vida», reza el texto, escrito en griego clásico, compuesto junto a un esqueleto tumbado a la bartola al que acompañan una jarra de vino y una hogaza de pan.

(Hurtado, 2016)

Y después de esto, no hay mucho más que decir.

Mil gracias a ti por leer y a Pequeña Antimateria, no solo por preguntar, si no, por crear y cuidar este precioso espacio consagrado a la curiosidad apasionada.

To sing in the literal sense, listen to Los Diablos (Rojos), who play like this... and give name to the four categories into which this Pequeña Antimateria is divided, listed at the beginning of their song El Guapo. An absolute banger that delivers on its promise, complete with the incredible devilish shouts and laughter of Lucho Carrillo. Unmissable.

To sing in the figurative sense, an idea that underlies all these articles—and one that was already perfectly summed up and illustrated 23 centuries ago by the person who created this mosaic: The recent discovery of a 3rd-century BCE mosaic in southern Turkey, bearing a particular message (...), has surprised even archaeologists. “Be cheerful, live your life,” reads the text, written in classical Greek, set beside a skeleton lounging lazily, accompanied by a jug of wine and a loaf of bread.

(Hurtado, 2016)

And after that, there’s really not much more to say.

A thousand thanks to you for reading, and to Pequeña Antimateria—not just for asking questions, but for creating and nurturing this beautiful space devoted to passionate curiosity.