La newsletter de esta semana nos ha emocionado profundamente. Su fuerza narrativa, evocadora y desafiante, llena de energía para la acción, encarna a la perfección el espíritu con el que queremos enfrentar este otoño. Espero que la disfrutéis tanto como nosotras.

---------

This week's newsletter has moved us deeply. Its evocative, bold, and action-ready narrative perfectly aligns with the spirit with which we want to approach this fall. We hope you enjoy it as much as we do.

Donatella Cusmá es arquitecta y educadora. Creció en Sicilia, donde las capas de historia formaron su apreciación por el palimpsesto cultural y despertaron su curiosidad por las culturas extranjeras y las peculiaridades locales. Es socia principal del estudio de arquitectura Claret-Cup, con sede en Los Ángeles, que cofundó con Bojana Banyasz en 2014. Donatella es miembro del Research Institute for Experimental Architecture y forma parte de la junta directiva del Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design. Su trabajo es sabio, generoso, divertido y amable pero sin ser complaciente. Una gran inspiración en una ciudad tan centrada en si misma como Los Angeles.

wwww.claret-cup.com

www.instagram.com/donatella_cusma

----------

Donatella Cusmá is an architect and an educator. She grew up in Sicily where history influenced her appreciation of the cultural palimpsest and fostered a curiosity for foreign cultures and local oddities. She is a principal of Los Angeles based architectural studio Claret-Cup that she co-founded with Bojana Banyasz in 2014. Donatella is a Board member of the Research Institute for Experimental Architecture and serves in the Boards of Directors of the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design. Her work is thoughtful, generous, fun, and kind, yet without being complacent—a great inspiration in a city as self-centered as Los Angeles.

4 ITEMS by Donatella Cusmá for PEQUEÑA ANTIMATERIA

.

ITEM #1 Salt Flats in Western Sicily

Las policromáticas salinas a lo largo de la costa de Trapani, en Sicilia, son paisajes fascinantes que hipnotizan y deleitan. Geología, economías geopolíticas, tradición, mito, hábitat y clima forman parte de la historia del “oro blanco”, profundamente sedimentada en la identidad colectiva de esta región del territorio siciliano.

La recolección de la sal, que ocurre anualmente entre los meses de julio y agosto cuando el sol es fuerte y los vientos amainan, se realiza a mano utilizando técnicas tradicionales. Estos exquisitos y singulares espacios de producción han estado en actividad casi continua durante siglos, desde la fecha estimada de su creación, en la época en que los fenicios se establecieron en la isla.

Desde un punto de vista elevado, como la terraza de un molino cercano, la cuadrícula irregular de las salinas, con sugerentes nombres sicilianos (caura, ruffiana, ruffianeddra, sintina, vasu, caseddra), delimita el territorio ofreciendo una esquiva sensación de escala, que se desvanece y reaparece según la rarefacción de las figuras humanas o de aves a lo lejos.

Este paisaje aparentemente bidimensional, plano y vasto, se encuentra con el mar en uno de sus bordes, invitándolo a entrar a través de una serie de canales arcanos. Seductoras y explícitas con su gloriosa paleta de colores, que va desde azules hasta rosados, naranjas y blancos opacos, la complejidad del ecosistema de las salinas se revela lentamente: una sensación de vida que se cuece por debajo y por encima de la costra salina emerge a un ritmo tranquilo y contemplativo.

Símbolo de resiliencia cultural y ambiental, este lugar acuoso, salado y rastrillado, aparentemente demasiado abstracto como para sugerir la posibilidad de vida, es, de hecho, una nueva frontera para las alianzas inter-especies y bioquímicas, donde microorganismos, crustáceos, aves migratorias y humanos coexisten.

-----

The polychromatic salt flats along the coast line of Trapani, in Sicily are fascinating landscapes that mesmerize and delight. Geology, geopolitical economies, tradition, myth, habitat, climate are part of the history of the “oro bianco”, and deeply sedimented into the collective identity in this area of the Sicilian territory.

The harvesting of the salt that occurs yearly between the months of July and August when the sun is strong and the winds subside, is carried out by hand using traditional techniques. These exquisite and singular spaces of production have been almost continuously active for centuries since the assumed date of their inception, around the time when the Phoenicians established themselves on the island.

When seen from a vantage point, such as the terrace of a nearby windmill, the irregular grid of the basins, bearing suggestive Sicilian names (caura, ruffiana, ruffianeddra, sintina, vasu, caseddra), measures the territory offering an elusive sense of scale, coming in and out of focus contingent on the rarefact presence of humans or birds, in the distance.

This seemingly two-dimensional landscape, flat and wide, meets the sea at one of its edges, inviting it in through a series of arcane channels.

Explicitly seductive with their glorious sets of colors, from blues to pinks to oranges and off-whites, the complexity of the salt pans’ ecosystem is revealed slowly: a sense of life brewing below and above the saline crust emerges at a quiet and contemplative pace.

A symbol of cultural and environmental resilience, this aqueous, brined, raked place seemingly too abstract to suggest the possibility of life thriving, is in fact a new frontier for interspecies and bio-chemical alliances, where microorganisms, crustaceans, migratory birds and humans coexist.

ITEM #02 Farm Cultural Park

En la provincia de Agrigento, no lejos del sitio arqueológico del Valle de los Templos, se encuentra la ciudad de Favara. Al igual que muchos pequeños pueblos sicilianos alejados de los centros turísticos, Favara vio una salida constante de su población joven debido a la falta de oportunidades económicas tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A medida que los residentes se marchaban, los edificios del centro histórico se deterioraron, algunos de ellos se desmoronaron en ruinas.

Hace catorce años, Farm Cultural Park nació de los esfuerzos de los filántropos, coleccionistas de arte y activistas comunitarios Florinda Saieva y Andrea Bartoli. Creyendo en el poder transformador de la educación, el arte y la cultura, buscaron revertir la caída de Favara lanzando un proyecto de renovación urbana en respuesta a la crisis económica y cultural.

Farm Cultural Park adoptó un enfoque autofinanciado y de base que evitó los a menudo lentos e ineficientes procesos burocráticos típicos de la administración pública italiana. Adquirieron varios edificios en ruinas alrededor de siete patios en el corazón de Favara, una configuración que recuerda a una Kasbah siciliana (I Sette Cortili), y los transformaron en espacios culturales y comunitarios vibrantes. Estos ahora albergan galerías interiores y exteriores, bibliotecas, aulas, áreas de exhibición, una tienda de regalos y un café/bar. Los negocios locales comenzaron a prosperar alrededor de la granja, con la aparición de alojamientos, restaurantes, panaderías y cafés.

Los programas de la granja involucran a artistas, escritores, arquitectos y educadores locales e internacionales, ofreciendo residencias artísticas, una escuela de arquitectura para niños, una escuela de política para niñas, un centro cultural y una biblioteca para adolescentes, e incluso una embajada para no humanos. Además, la organización ha publicado un manual para "arquitectos post-humanos".

Desde que la descubrí por primera vez en 2015 durante un programa de estudio en el extranjero con colegas y estudiantes de la Universidad de Woodbury, he regresado varias veces a Farm Cultural Park en Favara. Cada visita renueva mi admiración por esta institución ética, provocadora y visionaria.

Una de mis instalaciones favoritas está dentro del Palazzo Micciché, un edificio aristocrático de finales del siglo XIX que estuvo abandonado durante 60 años antes de ser salvado por la granja. La última vez que visité este espacio fue a finales de primavera, durante una de las sequías y olas de calor más severas que Sicilia ha experimentado en los últimos años. Los vientos del Scirocco habían soplado, cubriendo todo, incluidas las bocas de las personas, con un polvo rojizo familiar. Los coches embarrados permanecieron sin lavar, los tanques de agua de lluvia en los tejados estaban medio vacíos, esperando la visita de la unidad móvil de recarga. Las sábanas colgadas en las líneas de ropa ondeaban como banderas blancas en el viento caliente, protegiendo la ropa del polvo omnipresente

------

Farm Cultural Park was born 14 years ago from the initiative of two philanthropists/art-collectors and community activists who believed in the power of education, art and culture to reverse the fate of Favara. Founders Florinda Saieva and Andrea Bartoli set in motion an urban rejuvenation project in response to the economic and cultural crisis that affects the town.

Deploying a self-funded, self-organized, bottom-up strategy, the organization operates autonomously from the lethargic and obtuse bureaucratic processes that characterize most Italian administrations and the public sector.

Several buildings, organized along seven courtyards in the dilapidated center of Favara forming a sort of Sicilian Kasbah (I Sette Cortili) were acquired, renovated and transformed into a cultural and community center with indoor and outdoor galleries, libraries, classrooms, exhibition spaces, a gift shop and a bar/café. Local businesses coalesced around the Farm, and other enterprises, such as bed & breakfasts, restaurants, bakeries and cafes flourished.

The Farm runs several programs and initiatives with local and international artists, writers, architects and educators, including artist residencies, a school of architecture for children, a school of politics for girls, a cultural center and library for teenagers, instituted an embassy for non-humans and published a toolkit for “post-human architects”.

I have been back in Favara and at Farm Cultural Park several times since stumbling upon it while on a Study Abroad program with colleagues and students of Woodbury University in 2015. Every visit renews my admiration for such an ethical, provocative and illuminated institution.

One of my favorite artworks is a permanent installation located inside Palazzo Micciché, a late 19th-century aristocratic building that languished abandoned for 60 years before being acquired and saved from its decrepitude by Farm Cultural Park.

I last visited this space late in spring, in one of the most severe droughts and heat-waves that Sicily has experienced in recent years. The Scirocco had blown in the days preceding my visit, covering every surface and cavity - including people’s mouths - in the familiar powdery, reddish sand. Muddied cars were left unwashed, the colorful rain tanks punctuating the roofscapes of the town languished half empty until the visit of the mobile refill unit. Plastic sheets covering clothing lines to preserve the laundry from the insidious dust, blew in the hot wind like white flags.

The perceivable drop in temperature meets you like a long-lost friend, as you enter the Human Forest from the steep and narrow stone-paved road leading to palazzo Micciché. Here, a multidisciplinary collective of architects, botanists, psychologists and musicians, planted the permanent installation. A reflection on climate change and the relationship between nature and humans, the installation is comprised of hundreds of plants and trees representing over twenty different species. Planted within the ancient walls of the palazzo and taking advantage by the collapsed second floor to allow room for the trees to grow, soaring towards intelligently placed skylights that let water and light in, the space welcomes insects, birds and humans alike.

ITEM #03 Ə

No fue hasta que me mudé de Italia a un país de habla inglesa cuando comencé a reflexionar sobre el poder del lenguaje para mostrar asimetrías y sesgos de género, y para perpetuar la desigualdad y exclusión de género.

Mis viajes periódicos a Italia, en su mayoría en verano, durante los últimos dieciocho años, siempre han sido una mezcla de ansiedad y emoción. En el momento en que el avión toca tierra italiana, pero antes de que se apague la señal de "cinturón de seguridad", las conversaciones telefónicas estallan en una cacofonía de declaraciones, preguntas, estrategias de encuentro e instrucciones. Mientras el sonido familiar de las palabras en italiano me recibe, me doy cuenta de que las personas de mi género son en gran parte borradas por la propia naturaleza del idioma.

El uso del masculino genérico es omnipresente, adoptado casi sin discernimiento por hablantes de todos los géneros. La presencia de una sola persona que se presenta como masculina en un grupo dicta el género de los términos utilizados: "i ragazzi", "gli studenti", "i passeggeri", "gli architetti", y así sucesivamente. La evocación predominante del masculino limita la visibilidad de las personas femeninas y no binarias, borrando su identidad.

Si se les pregunta al respecto, muchos hablantes de italiano dirían que el masculino genérico es inherentemente inclusivo, que es solo una simplificación, una convención que representa a todos. Estas son las mismas personas que me miran con desconcierto si sugiero cambiar, por un tiempo, al uso del femenino genérico. ¿Cómo se sentirían la mayoría de los hombres si nos refiriéramos a un grupo de géneros mixtos como “le ragazze”, “le studentesse”, “le passeggere”, “le architette”? ¿Qué pasaría si generación tras generación de estudiantes se sentaran en aulas donde la palabra "mujer" se usara indistintamente con “humanidad”?

Por esta razón, tengo muchas esperanzas en el potencial de usar la schwa (Ə) en el idioma italiano para promover una lengua más equitativa e inclusiva. El lenguaje tiene un papel fundamental en nuestra percepción de la realidad, en la formación de nuestro sentido de identidad y afecta la manera en que entendemos nuestro rol en la sociedad, nuestras libertades, nuestra confianza, nuestros derechos. Un lenguaje inclusivo es un pacto de representación y aceptación.

Así que esto es una oda a la schwa, a las promesas que contiene, a lƏ ragazzƏ, passeggerƏ, architettƏ, y a un futuro más inclusivo y justo para la humanidad, donde las personas de todos los géneros se sientan incluidas, representadas y seguras.

--------It was not until I moved to an English-speaking country from Italy that I started to reflect on the power of language to exhibit gender asymmetries and biases, and to perpetuate gender inequality and exclusion.

Periodic trips to Italy, mostly in the summer, over the past eighteen years, have always been a mix of trepidation and excitement. The minute the plane touches down on Italian ground, but before the “seat belt on” sign is turned off, the cell phone conversations erupt in a cacophony of statements, questions, meeting-point strategies and instructions. As the familiar sound of Italian words greet me, I am reminded that people of my gender are largely erased by the very nature of the language.

The use of the overextended masculine is pervasive, adopted almost without discernment by speakers of all genders. The presence of a single male-presenting individual in a group, dictates the gender of the terms used: “i ragazzi”, “gli studenti”, “i passeggeri” “gli architetti”, and so on. The predominant evocation of the masculine limits the visibility of female and non-binary individuals, erasing their identity.

If asked about it, many Italian speakers would say that the overextended masculine is inherently inclusive, it is just a simplification, a convention that represents all. These are the same people who give a me a blank stare if I suggest to switch, for a while, to an overextended feminine. How would most men feel if we would refer to a group of mixed genders as “le ragazze”, “le studentesse” “le passeggere”, le architette? What if generation after generation of students would sit in classrooms where the word “woman” was used interchangeably with “humankind”?

For this reason, I have a lot of hope for the potential of using the schwa (Ə) in the Italian language to promote a more equitable and inclusive Italian language. Language has a fundamental role in our perception of reality, in forming our sense of identity, and affects the way we understand our role in society, our freedoms, our confidence, our rights. An inclusive language is a pact of representation and acceptance.

So this is an ode to the schwa, to the promises it holds, to lƏ ragazzƏ, passeggerƏ, architettƏ, and to a more inclusive and just future of humankind, where people belonging to all genders feel included, represented and safe.

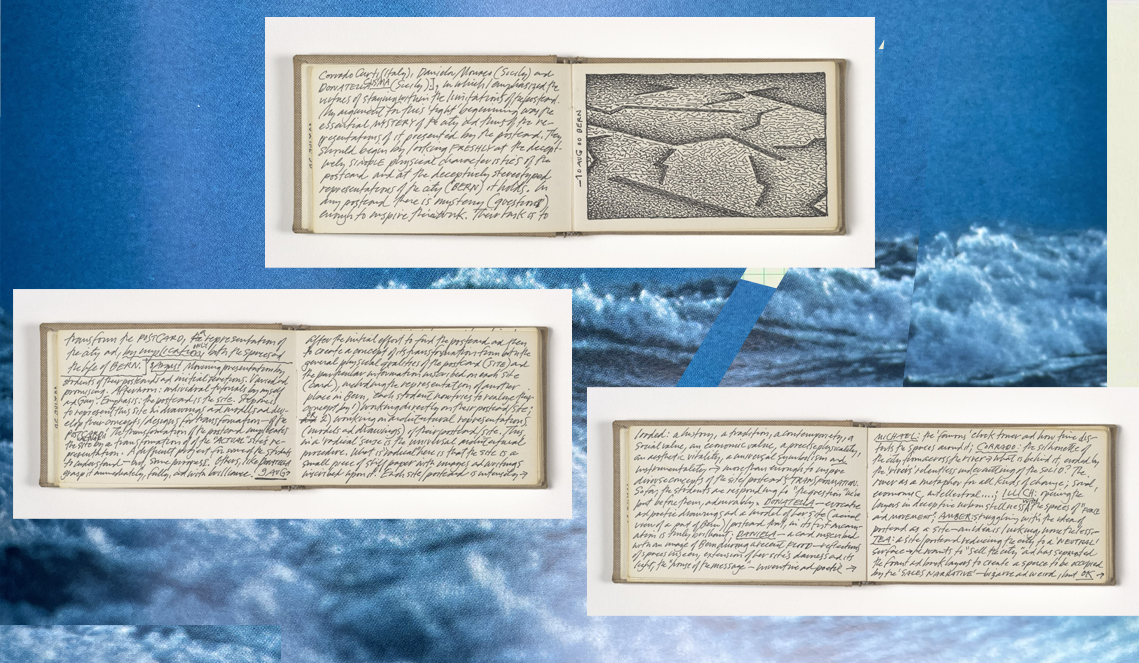

ITEM #04 Resistance

Tuve el placer de estudiar con Lebbeus Woods en Suiza. Fue un maestro generoso y apasionado. Amaba a sus estudiantes, y nosotros lo amábamos a él. Sus conferencias eran radicales, fascinantes y transformadoras, alterando permanentemente nuestra comprensión de la disciplina y los valores que ésta sostiene.

Lebbeus tenía una estatura imponente, tanto física como intelectualmente, y sin embargo trataba a cada estudiante como un igual. Entraba al aula con una palpable sensación de urgencia, infundiendo el deseo de saber más, de hacer conexiones, de formular preguntas, de leer, escribir, dibujar y crear frenéticamente, de cuestionarlo todo y de abrazar el trabajo con un rigor extremo.

Tuvimos tantas conversaciones profundamente interesantes, acompañadas de vino y cigarrillos, en la escuela independiente que él nombró RIEA (Instituto de Investigación para la Arquitectura Experimental), tantas lecciones aprendidas, todas ellas aún resuenan y perduran. Forman un reservorio de inspiración y consejo que sigue dando frutos, reapareciendo continuamente.

Lebbeus parecía prosperar e interesarse por lo invisible, lo desconocido, por situaciones incómodas y preocupantes. Escribió sobre la arquitectura en relación con la guerra, la política y la justicia social. Le interesaban los problemas difíciles, aquellos que exigen ser más atentos, más ingeniosos, que requieren montar una resistencia digna y ética.

En su "lista de resistencia" escribió: Resiste lo que parece inevitable. Resiste a quien se siente invencible. Resiste el impulso de tomar el camino de menor resistencia.

Hace unos días se cumplió el día en que comienza la novela distópica de Octavia Butler Parábola del Sembrador. El libro es inquietantemente profético: desastres climáticos debido al cambio climático, inequidades raciales, de género y de clase, esclavitud, políticos demagogos con agendas fascistas y la guerra están devastando la sociedad. Un relato de advertencia que se siente demasiado cercano a nuestra realidad actual.

(Re)penso en la lista de resistencia de Lebbeus y su invitación a resistir. No creo que pretendiera aplicarla solo a la arquitectura, y ciertamente, estas palabras, escritas hace varios años, suenan como un excelente consejo en los tiempos que vivimos hoy.

https://youtu.be/j1JMNIFYZnc?si=wqjKCe8C4l9ekv--

-----

I had the pleasure of studying under Lebbeus Woods in Switzerland. He was a generous and passionate teacher. He loved his students, and we loved him. His lectures were radical, enthralling and transformative, permanently altering our understanding of the discipline and the values it holds.

Lebbeus had a towering stature, both physically and intellectually, and yet he treated every student like his peer. He entered the classroom carrying a tangible sense of urgency, instilling the desire to know more, to make connections, to ask questions, to read, write, draw and make feverishly, to question everything, to embrace the work with extreme rigor.

So many deeply interesting conversations were held, with wine and cigarettes, at the independent school that he named RIEA (Research Institute for Experimental Architecture), so many lessons were learned, all of them still resonate and linger. They form a reservoir of inspiration and advice that keeps on giving, continuously resurfacing.

Lebbeus seemed to thrive and be interested in the invisible, in the unknown, in situations that are uneasy and worrisome. He wrote about architecture in relation to war, to politics to social justice. He was interested in a difficult problem, one that demands of you to be more attentive, more resourceful, one that requires you to mount a dignified and ethical resistance.

In his “checklist of resistance” he wrote:

Resist whatever seems inevitable.

Resist who feels invincible.

Resist the urge to take the path of least resistance.

A few days ago, marked the day in which the dystopian novel by Octavia Butler “Parable of the Sower” begins. The book is eerily prescient: disastrous weather events due to climate change, racial, gender and class inequities, slavery, demagogue politicians with fascists agendas and war are ravaging society. A cautionary tale that hits too close to home in today’s times.

I (re)think of Lebbeus’ checklist and his invitation to resist. I don’t think he meant for it to apply to architecture alone, and for certain these words, written several years ago, sound like really good advice, today.